Learning how to think is one of the most important skills one can develop in this life. Unfortunately, much of formal education does not prepare or encourage you to foster this skill. At least that was our experience, save for a few exceptional teachers we were fortunate to have.

Reading about mental giants of the past and present greatly aids in seeing how elevated thinking works. People like Benjamin Franklin, Richard Feynman, and Charlie Munger are all mental giants whose writing and speaking have provided innumerable benefits to many. One practice that these luminaries cultivated was the utilization of mental models.

Mental models are a framework of tools to help you think better. But just as a house cannot be built with only a hammer, relying on one mental model for all facets of life will hardly provide ideal results. Instead, numerous mental models must be mastered and simultaneously deployed to improve thinking.

You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience – both vicarious and direct – on this latticework of models.

– Charlie Munger

Throughout history, people have been fascinated with how to think. As such, much thought and effort have been expended into understanding and improving thought processes. We can, and should, master what those before us have created and then build off of it. Instead of reinventing the wheel, it is a much more productive use of time to learn, internalize, and apply what others have already learned. It’s like taking a shortcut.

If I have seen further, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.

– Sir Isaac Newton

I believe in the discipline of mastering the best of what other people have ever figured out. I don’t believe in just sitting down and trying to dream it all up yourself. Nobody’s that smart.

– Charlie Munger

There are many mental models, but below are the general models that we know and use every day. Learning about each one is like acquiring a new tool. It’s a great to keep adding new tools to one’s toolbelt, but practice is required in order to become adept at its usage.

The Map is not the Territory

Reality is a mental construct. We can’t process everything around us, so we are reliant upon mental maps. Maps are simplifications of the reality around us, accurate enough to allow us to navigate but simple enough to be usable. We are all cartographers in our own world, and we rely on the maps of others as well. But once we become too reliant upon maps, or believe them to be more accurate than they really are, we can get into trouble. This mental model reminds us that our perception of the world is a simplified understanding that, while useful, is flawed.

Just as we can look at an image and see things that aren’t really there, we can look out into the world with skewed perceptions of reality.

– Brian Resnik, Vox

We have this naïve realism that the way we see the world is the way that it really is.

– Emily Balcetis, Vox

Probabilistic Thinking

Probabilistic thinking is trying to estimate the likelihood of an outcome, and it is an immensely powerful way to think of the world around us. Life is dynamic and things change. Classifying something as certain is a fool’s errand. Instead, there are an infinite number of possible scenarios that could be an outcome to a decision or action, and it behooves you to view the world in that vein. There are a few things that can trip you up when it comes to employing probabilistic thinking, though. Some include causation versus correlation, black swan events, probabilistic asymmetries, and fat-tail distributions. The analytical mind needs to understand what can be controlled and account for them. But in the end, just because something is likely doesn’t mean that it will occur. That’s why it’s important to use a margin of safety (or in the engineering world, a safety factor) to buffer the chance of being wrong.

It is better to be vaguely right than exactly wrong.

– Carveth Read, British philosopher

Thought Experiments

Thought experiments open up avenues of inquiry and creativity to imagine what is possible. They allow us to identify potential consequences down the road based upon a set of decisions made to today. These experiments are like the choose your own adventure books where you get to choose potential future events and take various turns at each juncture. Like those books, if you read ahead and don’t like your decision, you can flip back to the last fork in the book and choose another option. You become a mental time traveler, exploring future potentialities. Your experiments are influenced by your past experiences – both mistakes and successes – to aid in better decision making.

Second-Order Thinking

Similar to thought experiments, second-order thinking (sometimes referred to as second-level thinking) looks into the future to take into consideration the knock-on effects of a decision. In other words, it tries to identify unintended consequences (good or bad) of a decision or action. Stated yet another way, second-order thinking deals with the effects of the effects of a decision or action. The immediate, intended result of a decision is relatively easy to identify. Second-order thinking, however, is complex and intensive. Many factors must be taken into account for second-order thinking, such as the range of likely outcomes, which outcome is likely to occur, how people will behave, and so on. Each iteration (third-order, fourth order, etc.) becomes exponentially more complex, and generally only second-order (and occasionally third-order) thinking is productive. Attempting to derive numerous iterations beyond second-order thinking usually yields paralysis by analysis.

Spectral Thinking

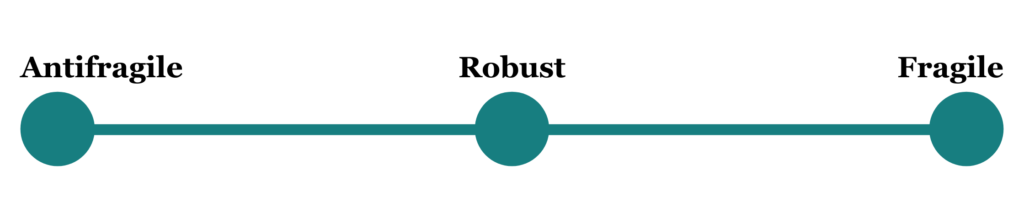

To us, spectral thinking is viewing classifications on a spectrum. Nassim Taleb writes about this in his book Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. In the book he says that people think of robust as being the opposite of fragile. Taleb says that this is incorrect because fragile things lose from disorder. Robust things can withstand disorder, but they do not gain from it. The opposite of fragile would be something that gains from disorder. Therefore, Taleb identifies antifragile as the opposite of fragile. That is spectral thinking. Those who were only seeing fragile and robust missed an entire other part of the spectrum.

Circle of Competence

Each of us has a circle of competence. Within that circle, we are likely to make better decisions because we are intimately familiar with the subjects. Once we step outside our circle of competence, we are venturing into a realm we do not fully understand. If we do not quiet our egos and accept that we are dealing with things outside of our expertise, we vastly increase our odds of making a poor decision.

What an investor needs is the ability to correctly evaluate selected businesses. Note that word, “selected”: you don’t have to be an expert on every company, or even many. You only have to be able to evaluate companies within your circle of competence. The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital.

– Warren E. Buffett, 1996 Shareholder Letter

A curious byproduct of learning is that as you learn, your circle of competence grows, meaning that your perimeter of ignorance grows as well. Said another way, the more you learn, the less you know.

The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don’t know.

– Albert Einstein

First Principles

A first principle is a basic assumption or idea that cannot be deduced any further. Aristotle defined it as, “the first basis from which a thing is known”. First principles differ between people. For example, theoretical scientists must break down some laws of science for further discovery whereas an engineer can use the laws of gravity, electricity, etc. as first principles to design a structure. Shifting the way you think to challenge your inherent assumptions can help you pursue first principles in your life.

My painful mistakes shifted me from having a perspective of ‘I know I’m right’ to having one of ‘How do I know I’m right?’

– Ray Dalio

Start with the Definition

Similar to first principles, starting with the definition aims to identify a foundation upon which you can build. Whereas first principles thinking deals with the basic facts, starting with the definition is getting two or more people to agree on the meaning of something. Language is fluid and words mean different things to different people. Therefore, it is important to begin with agreeing upon a definition, even if only temporarily, in order to engage in meaningful communication.

Inversion

Inversion is the practice of turning a problem upside down or starting at the end. Imagine the problem as an object in your hand. You can turn it all sorts of ways to better understand it. That’s what inversion does. When you are stumped, change your view to a different angle and attack it again. In seeking first principles, Ray Dalio also inverted his thinking. Many investors and business people understand that instead of seeking success, they should avoid failure – that is, permanent failure. You too can improve your thinking by learning to invert.

Man muss immer umkehren [Invert, always invert].

– Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, German Mathematician

Start then Optimize

Overcoming inertia is difficult. But Newton’s First Law of Motion works both ways. An object at rest tends to stay at rest and an object in motion tends to stay in motion. So too does this apply to thoughts and ventures. It is enormously beneficial to quiet the perfectionist within so many of us in order to get moving in the right direction. Moreover, once you start, you may decide that this was the wrong decision, and you scrap the idea. Failing fast is critical from an opportunity cost perspective. If you strive for starting with perfection, and then you realize later that starting this endeavor was the wrong decision, you have wasted the finite resources of your time and energy that you otherwise could have used for more productive means. This model is something we have relied upon heavily for Palladian Park. We have iteratively been working on Palladian Park for over a year, bit by bit, slowly but purposefully optimizing. And it’s not perfect. We envision Palladian Park as forever a work in progress. But that’s the point. If we had waited until we thought it was perfect, Palladian Park would not exist.

Perfect is the enemy of good.

– Voltaire

Occam’s Razor

Occam’s Razor is a champion for the simple. It posits that simpler explanations are more likely to be true than complicated ones. This is a great strategy to use when trying to select a correct possible explanation amongst many, or it can be paired nicely with probabilistic thinking.

A plurality is not to be posited without necessity.

– William of Ockham, medieval logician

Hanlon’s Razor

Hanlon’s Razor has immense value for interacting with others in a deeply polarized world. It states that one should not attribute to malice that which is more easily explained by stupidity or ignorance. A wonderful byproduct of using Hanlon’s Razor is that it reduces paranoia and anxiety. You see the world around you as good intentioned but sometimes misled. A good example of this is someone who shares a bogus post on social media. They probably aren’t evil, they are likely ignorant or don’t understand. Incorporating this into your thinking allows you to sympathize and empathize with others around you more easily.

Stupidity is the same as evil if you judge by the results.

– Margaret Atwood, Canadian poet

Follow Incentives

Most people have probably heard the phrase, “follow the money”. While this is applicable in many instances, it should be noted that money is only one incentive. There are many other incentives that influence what people say and do. Understanding the factors that influence behavior in yourself and in others provides clarity as to why things are often done the way they are. Similar to Hanlon’s Razor, this model differentiates between a person being inherently bad and instead shows that we can all be influenced by numerous internal and external incentives.

Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.

– Charlie Munger

Mental Models Change You

Overall, mental models change the way that you view the world for the better; they move you in the direction of mastery. And while mastering mental models won’t lift the fog of uncertainty in life, it will help you navigate within it.

When you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.

– Dr. Wayne Dyer

One should always be striving for improvement. But there is a responsibility that comes with improvement. The bar raises for oneself. We are responsible for what we know, so when we aim to learn more everyday, our responsibilities grow.

But our abilities grow too. We can summit bigger mountains. We can dive deeper into the abyss. We can avoid hazards that trip up others. And most importantly, we can provide more value – whether it be inspiration, knowledge, or friendship – to those around us. Mental models are invaluable.

Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.

– Maya Angelou