In falconry, yarak is the state that falcons must be in for their best hunting. It is a hyper-alert condition where the falcon is hungry enough to want to hunt, but not so hungry that it’s too weak to do so. In yarak, the bird is solely focused on hunting, motivated to feed its hunger and stave off starvation.

Yarak can be represented on a spectrum. Starvation is on one end of the spectrum, where the animal is deficient in energy. Contentment is on the other end, where the animal has no motivation to find food. Yarak is the confluence of particular conditions that motivate optimal performance.

The yarak phenomenon is not singular to falcons. It exists in different forms in each of us as well. But we have a differentiator. Whereas falcons are only passively affected by external stimuli, we humans can actively create constraints to encourage a yarak-like state in ourselves and others.

Designing for Yarak in Ourselves

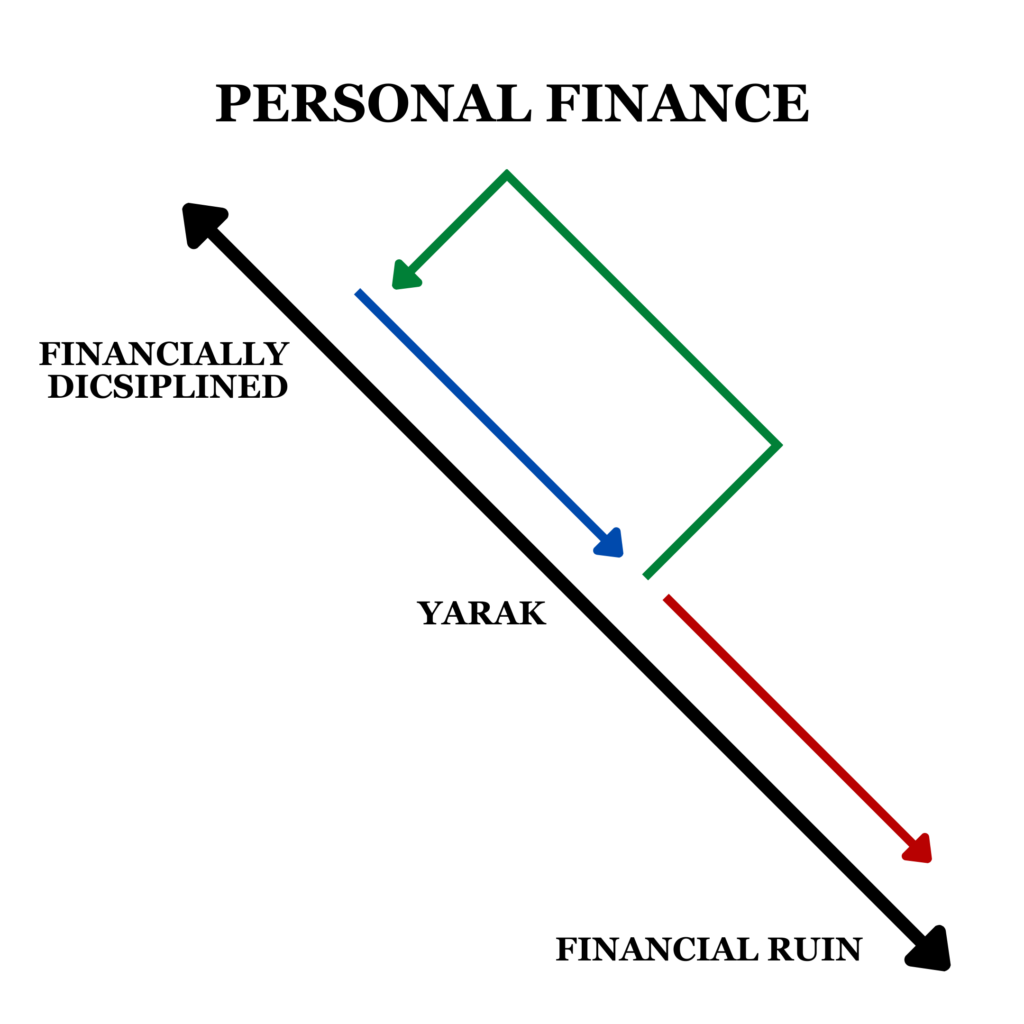

We can enter yarak in a variety of forms. One that affects nearly everyone is money. When it comes to personal finance, there is a popular strategy called “Pay Yourself First” where a percentage of your income is automatically moved to a savings account. Then you are constrained with what money you have left over to cover expenses.

Jake Taylor covers this style of yarak in The Rebel Allocator. In that book he writes:

[Pay yourself first is where] you take money out of your account every month in an automated way to save for the future and then live on whatever’s left. Pay yourself first before you pay everyone else. Sometimes you have to get creative to make ends meet and not dip into your savings. You create an artificial constraint, a hunger, this state of yarak in yourself. Yarak sparks creativity that can only be unlocked when your back is against the wall. You become the bird that has to hunt.

Designing for Yarak in Others

In 334 BC, Alexander the Great led a fleet of ships across the Dardenelles Strait to invade Persia. After landing, Alexander’s forces discovered they were vastly outnumbered. Alexander feared retreat would tempt his men so he ordered his fleet’s boats to be burned. Upon issuing this order, Alexander reportedly said, “We will either return in Persian ships or we will die here.”

In 1519, Hernan Cortez landed on the Yucatan shores to steal the riches of the Aztecs. He had fewer than 1,000 men to take on the entire Aztec empire. Understandably, some of Cortez’s men were unenthused and plotted to sneak away in the ships to nearby Cuba. But Cortez discovered their plan and had his ships burned.

Vikings and others have reportedly employed similar boat-burning strategies.

By burning the ships, each group entered a state of yarak. Every sense became trained upon the goal of living, which was only achievable with a victorious battle. Retreating wasn’t an option anymore. The sea became a wall, and their backs were up against it.

Ordering the ships to be burned was a risky move that could have ended in failure. It worked out for Alexander the Great and Hernan Cortez, but it easily could have turned out differently. Understanding the very real potential for failure and death galvanized and united the troops in their efforts to fight. They were in yarak because of the actions of their leader.

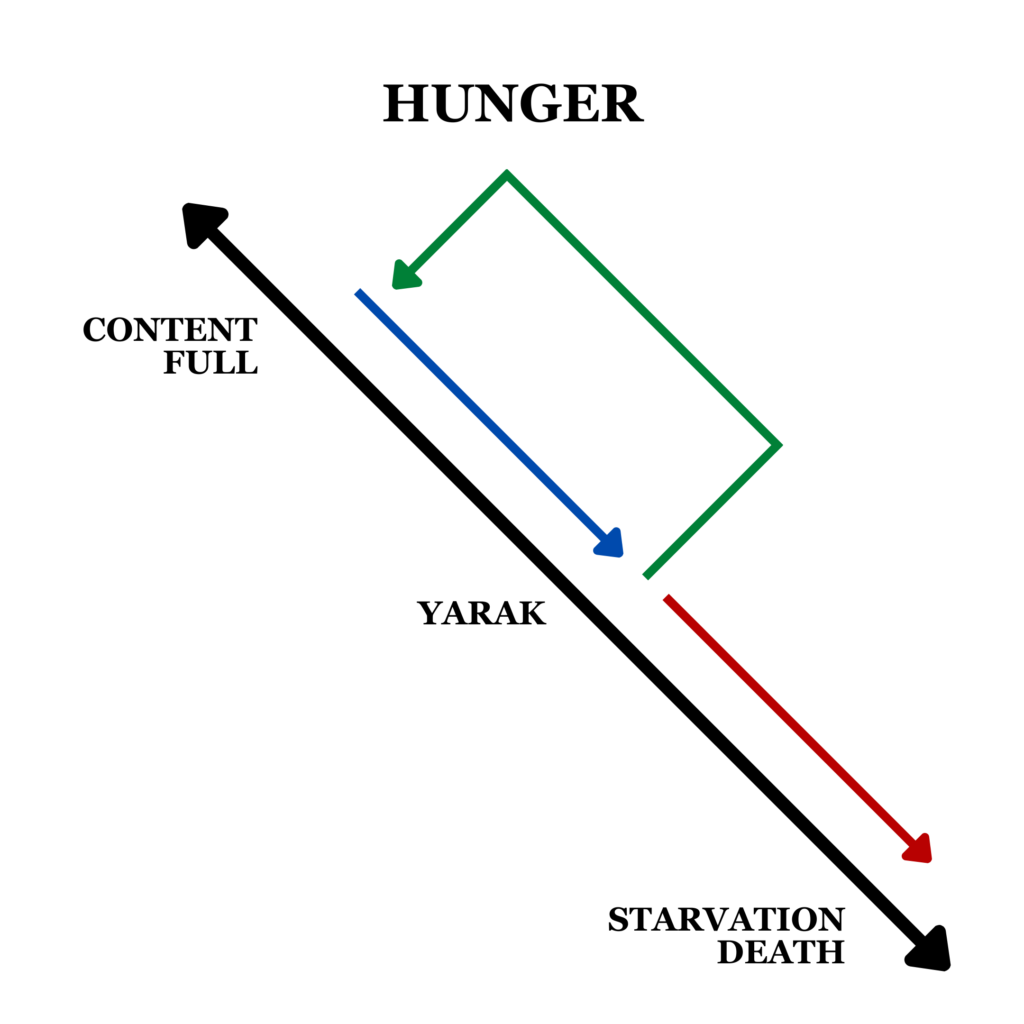

The Spectrums Aren’t Flat

In yarak, you are hyper-focused on achieving a particular result. You are in the middle of a spectrum where on one end lies death and on the other is contentment.

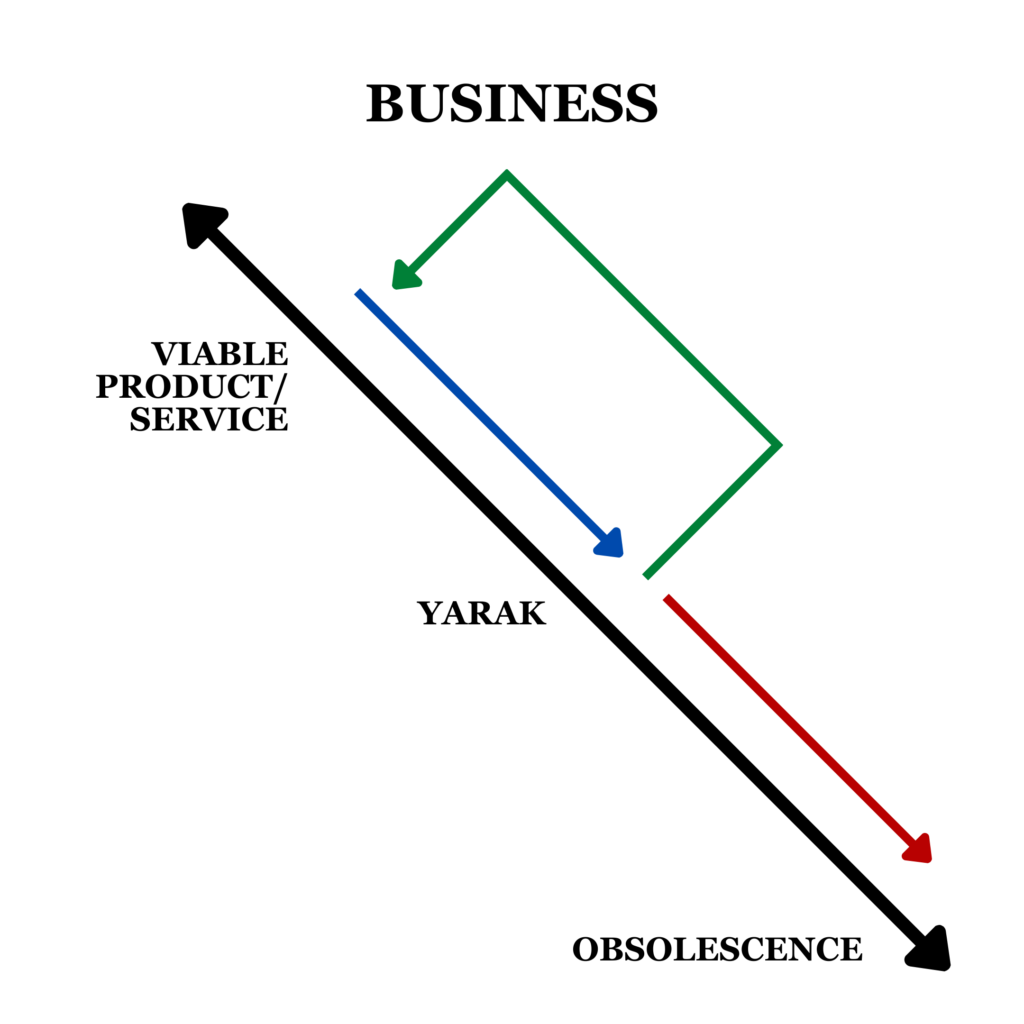

Returning to falcons, their yarak spectrum isn’t flat. It’s tilted. Contentment is at the top and starvation is at the bottom. Like with gravity, the animal’s state moves from the top (fully fed and content) downwards into yarak, the state of hunger that’s great enough to motivate the animal to hunt, but not so much that it’s too weak to do so. This is illustrated with the blue arrow in the diagram below. From there, hunger will continue to grow, pushing the animal into starvation and ultimately death. That portion is shown with the red arrow in the diagram below. But the animal can fight the downward-pulling grip of starvation. By hunting and eating, the animal returns to the top of the spectrum, until enough time passes when the animal is hungry again. This is captured with the green arrow in the diagram below. On and on this cycle repeats.

Yarak is effective when it comes to food precisely because of the consequence the animal faces if their hunt fails. Knowing that there is no return from failure attunes all of the animal’s senses to finding food.

Yarak is similar for people. With money, failure to save properly could result in financial ruin. In the case of Alexander the Great or Hernan Cortez with their troops, failure to fight tenaciously would result in death. Knowing these potential consequences exist is a powerful motivator.

It’s the same story for business. Competitors will assail any advantage you achieve, meaning you have to keep iterating to stay relevant. Stopping once you’ve achieved something is enticing but foolish. And if taken too far, it often leads to downfall through obsolescence.

Conclusion

When it comes to yarak, remember this. When you slide from comfort closer to undesirable consequences, those consequences become more real. This is why yarak fuels performance: knowing that pain is around the corner is one hell of a motivator to do everything you can to avoid it. Furthermore, the pain at the bottom end of the yarak spectrum is oftentimes a one-way door, meaning that if you don’t succeed prior to arriving there, there is no return. It’s like falling into the trap of starvation and hitting rock bottom, knowing that you are doomed.

Yarak is uncomfortable, yet that is the key ingredient for motivation. It comes naturally to animals as described with falconry. It also comes naturally to all of us as outside forces move us from stability to instability. But we also have the means to artificially inject yarak into our lives. We can do so for ourselves and others, influencing the different ways we interact with the world around us. If we get these motivational systems right, we can make profound impacts on our lives, our organizations, and the lives of others. But getting it wrong often ends in catastrophe.

Yarak is powerful. It straddles the divide between success and death, meaning that magnitude of its outcomes is significant. Understand its consequences and use it wisely.