Biases affect how we interpret and process information. Everyone has biases as a result from years of evolutionary progress as well as previous life experiences. While learning about the different types of biases is a worthwhile pursuit, it can only help mitigate your tendency to fall prey to them. Alas, we cannot fully remove biases from our lives. Curiously, however, it is much simpler to spot biased thinking in others rather than in ourselves. Therefore it is critically important to have a group of advisors or confidants to bounce ideas off of in order to mitigate the effects of biased thinking.

The question is not what you look at, but what you see.

– Henry David Thoreau

The universe of known biases is vast and would make for an incredibly long post. So we instead opted for some of the more common biases that are easy to commit. Familiarizing yourself with these and other biases will improve your decision-making skills and make you much more valuable to those around you who value your input.

The sheer volatility of people’s judgment of the odds . . . told you something about the reliability of the mechanism that judged those odds.

– Michael Lewis, The Undoing Project

Action Bias

Action bias is our tendency to favor action over inaction. Often, this tendency to action can benefit us but it can also lead to hasty, poor decision-making. When we frequently respond with action as our automatic reaction without proper consideration and rationale to back it up, it can lead to many unintended consequences.

If a man knows not to which port he sails, no wind is favorable.

Seneca

Anchoring Bias

Anchoring bias is an effect where the first piece of information we receive influences our processing of subsequent information. We are tethered to the first piece of information – anchored – and we interpret new information in relation to the original information. An example of this is a sale. A TV that is priced at $1,000 might be too expensive for someone. But they might view that same TV as a good deal if it was originally priced at $2,000 and was marked down to $1,000. Anchoring bias is critical when it comes to negotiations. Oftentimes, that is why the first set of terms is so high or low, depending on which party starts. They are trying to anchor the other party to those terms so any move away from that is viewed as a positive for the other party.

Attentional Bias

Attentional bias is our tendency to focus on certain phenomena while simultaneously ignoring others. This bias comes about because of our inability to focus on a large number of issues at the same time. Major factors that affect our attention are time constraints, urgency, and our emotional and stress states. An example of attentional bias that many of us likely have experience with is grocery shopping when we are hungry. Our hunger distorts our decision making; we are biased into overselecting – getting more food than we need – as well as choosing highly palatable foods at the expense of other factors (e.g. nutrition or price) in pursuit of fulfilling our immediate desire for food.

Bandwagon Effect

The bandwagon effect is where people act or think in a certain way primarily because other people are doing it too. This bias affects decision-making in many different aspects of life, including politics, sports, fashion, and finance. When looking at the growth of the bandwagon effect, the rate of conversion to a particular idea, belief, or trend increases in proportion to the number of others who have already “hopped on the bandwagon”.

As collaborative, social beings it makes sense that we have a tendency to align our beliefs and behaviors with a group, but with this tendency comes the problem of herd mentality and groupthink. It’s easy to convince ourselves to follow a trend simply because others are doing it. That’s why it’s important to stop and take time to evaluate any popular belief, idea, or trend against your own values and beliefs to make sure it’s something you want to take part in.

Commitment Bias

Commitment bias (also known as escalation of commitment) is our tendency to remain committed to prior behaviors despite new evidence that our original choice no longer has desirable outcomes. A common occurrence of this bias is in failing business projects or ventures: the more resources (time, energy, money, etc.) we have invested into the failing project/venture, the more likely we will continue investing into it even as it is sinking.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for information that supports a belief that you already hold to be true. It’s a heuristic that Kahneman’s System 1 thinking (described in Thinking Fast and Slow) relies on to help us interpret information quickly. And it makes us feel good. Finding information that supports your beliefs makes you think you are right, and thus, smart. But it causes major blind spots. Removing tendencies to search for confirming sources to your inherent beliefs will aid in mitigating the impact of confirmation bias. To test the validity of your ideas, you should ideally seek out both confirming and challenging information while you act as a third party who judges the merits of both sides.

Did you ever read my words, or did you merely finger through them for quotations which you thought might valuably support an already conceived idea concerning some old and distorted connection between us?

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches

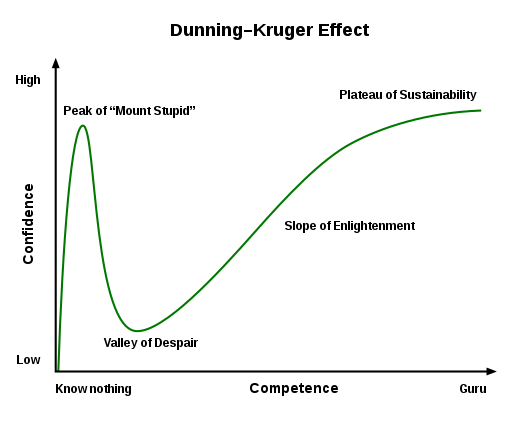

Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger effect is the phenomenon where ignorance tricks you into believing you are highly knowledgeable on a specific topic; you believe you have greater abilities than you really do. But as your knowledge grows, so too does your understanding of how much there is to know and where you actually fall on the spectrum. Becoming more knowledgeable makes you more humble, according to the Dunning-Kruger Effect. This plays into the circle of competence mental model: as your circle of competence grows, so too does your perimeter of ignorance.

*Source: Wikipedia Commons

It is impossible for a man to learn that which he thinks he already knows.

Epictetus

Familiarity Bias

Familiarity bias is the comfort we feel with what we know. We internalize the feeling of comfort with being right and discount the unknown due to the associated discomfort. This can get us in trouble in instances where an option outside of the familiar is the better choice, but we shy away from it and settle for what we know. While it is important to stick to your circle of competence when making a decision, you do have to venture outside of it in order for it to grow. Striking a balance of making important decisions within your circle of competence and intentional exploration outside of your circle of competence is necessary to limit bad decisions while also growing your knowledge base.

A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from the truth.

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

Framing Effect

The framing effect is where we base our decision making more on the way the information is presented to us rather than looking holistically at all the information. There are many different ways framing is implemented. Here are a few examples:

- Attribution Framing: Ground beef is 90% lean beef versus 10% fat.

- Risk Framing: Opportunity to save 85 out of 100 lives versus risk of losing 15 out of 100 lives.

- Goal Framing: Offering $10 reward versus imposing a $10 penalty.

Most often framing is used to draw our attention to the positive gain rather than the negative loss because humans are naturally loss averse, this is illustrated in the example above. Knowing this can help us guard against framing in our own lives. First, make sure you have all the relevant information and then invert all of said information. For example, if something is presented to you as having an 85% chance of gain, then invert this figure to say that there is a 15% chance of loss. When looking holistically at an issue, i.e. at both the possible positive gains and negative losses, you are less likely to fall victim to the framing effect and more likely to make a better decision.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias is where we look back at past events and assign a higher degree of likelihood that they were going to happen than what the odds were in reality; we are influenced by knowing that the events actually happened. This bias makes you think you are smarter than you really are, giving you a false sense of knowing something all along. That, in turn, negatively impacts your ability to identify the likelihood of future events. We all rely to a certain degree on past experiences to help us make decisions about the future. If our memory of the past is skewed by hindsight bias, then that can impede upon our future decision making abilities.

Fantasy. Lunacy. All revolutions are, until they happen, then they are historical inevitabilities.

David Mitchell, Cloud Atlas

Loss Aversion Bias

Loss aversion is where a loss is a more painful experience than an equivalent gain is pleasant. An example of this is finding $100 versus losing $100. Losing $100 results in a higher magnitude of emotion than finding $100 does. This bias applies to many areas in life, but it is maybe most applicable to how we make financial decisions. Knowing this bias is important in order to understand when you are unduly shying away from risk. You can do this by reframing the situation to take into account the likelihood of gain versus loss as well as the real magnitude of gain or loss.

Optimism/Pessimism Bias

Optimism bias is where we overestimate the likelihood of positive outcomes and underestimate the likelihood of negative outcomes. A few examples of this bias in action is when we think we will live longer than the average person or that our marriage won’t be one that ends in divorce. Optimism bias is also a major factor in why many big projects underestimate the cost and time a project will take.

Pessimism bias is the inversion of optimism bias: we overestimate the likelihood of negative outcomes and underestimate the likelihood of positive outcomes. While optimism bias is much more common, pessimism bias is still important to be aware of and understand.

Recency Bias

Recency bias entices us into believing recent events are more likely to occur again as opposed to other scenarios. We favor what we most recently experienced and project it into the future. Myopia is really what this is. Recency bias makes you nearsighted; you can see recent events in greater detail while events further in the past get a bit fuzzy.

Rosy Retrospection Bias

Rosy retrospection bias refers to our penchant to recall past events more fondly than the present ones. Another common way this bias is referred to is through the idiom, “seeing the world through rose-colored glasses”. This bias affects our perception of the past relative to the present and leads to an inaccurate understanding and distorted view of both time periods. Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign slogan, “Make America Great Again” plays perfectly into the rosy retrospection bias, calling for America to return to a better time, that may or may not have ever existed.

For as it turns out, one can revisit the past quite pleasantly, as long as one does so expecting nearly every aspect to have changed.

Amor Towles, A Gentleman in Moscow

Self-Serving Bias

Self-serving bias is the tendency to take credit for positive events or outcomes and blame external forces when negative events or outcomes occur. This is a defense mechanism humans have developed to protect our self-esteem. An example of this bias is when we get a good grade on a test in school we are likely to pat ourselves on the back and attribute the grade to our hard work. But if we fail a test we are more likely to make an excuse like the teacher didn’t prepare us well, the classroom was too cold, or we didn’t get enough sleep the night before.

Status Quo Bias

Status quo bias is the tendency to prefer the way things currently are over change. Loss aversion and familiarity biases play a big role in why status quo bias is an issue. Examples of status quo bias can range from incumbent politicians versus new contenders to a meal you order at a restaurant you frequent. It is also prevalent in business. If a new hire asks why something is done a certain way and the response is, “ because we’ve always done it this way,” that is status quo bias. Sometimes the best play is the status quo, but it shouldn’t be favored by default because it is the norm. Instead, it should be pitted against other options and evaluated on its own merits.

Silence isn’t neutrality; it is supporting the status quo.

Yuval Noah Harari, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century

Survivorship Bias

Survivorship bias is where we look to those who have succeeded in order to ascertain our likelihood of success. The problem with survivorship bias is that you are only looking at part of the spectrum. And when we don’t consider survivorship bias, our map does not accurately reflect the territory. Randomness (luck) plays a part in many aspects of life, including the likelihood of success in any given endeavor. By observing both those who have failed and succeeded, you can better devise your own course of action.

Biases are Ubiquitous

We all have biases; they are integral to life as we know it. But the degree to which we are biased can vary per bias per person everyday. Although biases cannot be eliminated, it is a noble pursuit to mitigate their effects in our lives. We mentioned that having a close circle of trusted advisors is immensely helpful in this endeavor. Mental models are another way to help. Broadening your life experiences is a third. But ultimately, we can only strive to improve.