Elite teams are comprised of high-performing people who trust each other. That’s the recipe: performance and trust. Although both qualities are important, one is much more so.

In The Infinite Game, by Simon Sinek, there is a section that delves into one of the most elite teams on Earth: the U.S. Navy SEALs. Admittance into the SEALs is incredibly rare. It requires grueling work that doesn’t let up once becoming a SEAL. But it might surprise you to learn that SEAL members are not necessarily the highest performing individuals. Instead, prospective SEALs are evaluated against two primary metrics: performance and trust.

The Difference Between Performance and Trust

Here’s how Simon Sinek contrasts performance and trust.

Performance is about technical competence. How good someone is at their job. Do they have grit? Can they remain cool under pressure? Trust is about character. Their humility and sense of personal accountability. How much they have the backs of their teammates when not in combat. And whether they are a positive influence on other team members.

A SEAL put it this way:

I may trust you with my life but do I trust you with my money or my wife?

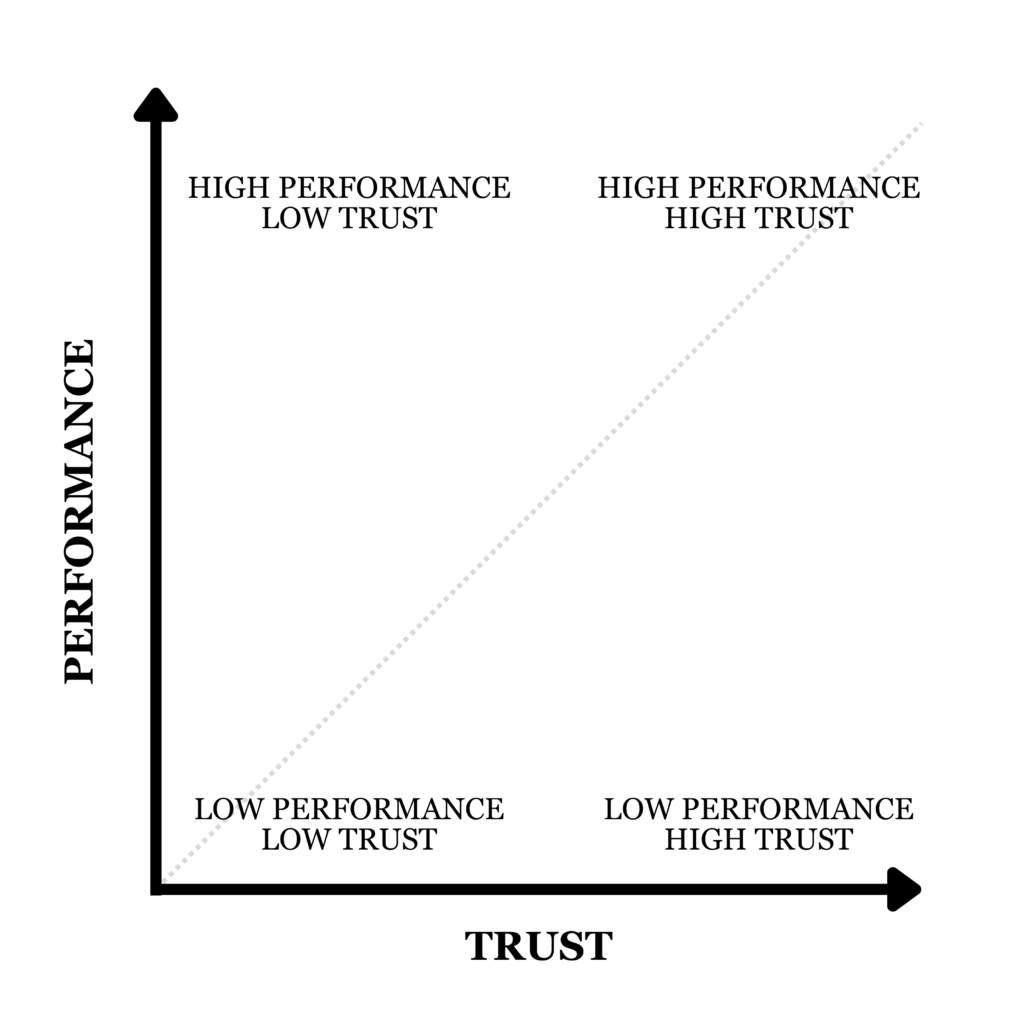

Graphing Performance vs. Trust

The Performance vs. Trust graph is a useful tool for evaluating how different people rate in both of these respective metrics.

In graphing performance against trust, it is clear teams want people whose plot is in the upper right corner; they are high in both performance and trust. It is likewise obvious that people in the lower left corner, being low in both performance and trust, are not ideal team members. But what about the other two?

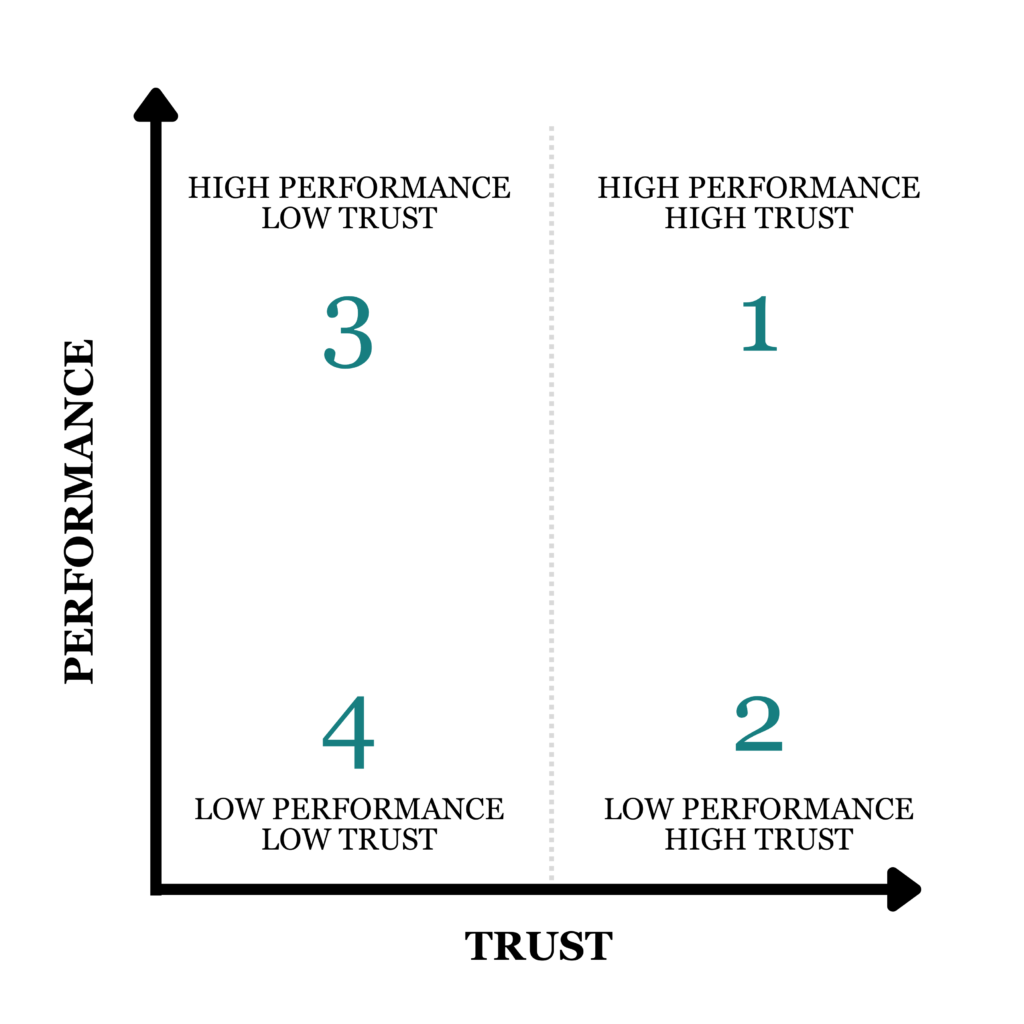

For the high performers with low trust, Simon Sinek writes:

What the SEALs discovered is that the person in the top left of the graph—the high performer of low trust—is a toxic team member. These team members exhibit traits of narcissism, are quick to blame others, put themselves first, “talk shit about others” and can have a negative influence on their teammates, especially new or junior members of the team.

And for the low performers with high trust:

The SEALs would rather have a medium performer of high trust, sometimes even a low performer of high trust (it’s a relative scale), on their team than the high performer of low trust.

So the types are prioritized as this.

Performance and Trust in Business

The U.S. Navy SEALs are a unique organization where their professional activities have little overlap with what the rest of us do in our daily lives. However, there is underlying wisdom in prioritizing trust over performance that is applicable in many situations. Business is one such situation.

Businesses are teams that work together to achieve a common goal. Because of the team aspect, the performance and trust metrics can be used to identify optimal team members. However, one’s performance capabilities are often overvalued when it comes to the business realm.

An example of a business prioritizing performance over trust is GE during the Jack Welch era. Welch had a system nicknamed “rank-and-yank” that rewarded solely performance. “Rank-and-yank” is exactly what it sounds like: rank the performance of employees and yank out (fire) the underperformers.

Like the SEALs, Welch also ranked executives on two axes. Unlike the SEALs, however, his axes were performance and potential; basically, performance and future performance. Based on those metrics, those who “won” biggest in a given year were earmarked for promotion. The underperformers were fired. In his drive to produce a high-performing culture, Welch focused on someone’s output above all else.

The performance metrics were relative, though, so it didn’t matter in absolute terms how well an employee performed. If they underperformed compared to other employees, they were removed from the organization.

It requires little imagination to see the incentives this system created. Instead of working to perform at their best, employees needed the performance of other employees to fall. Trust couldn’t grow in an environment like this, but a cutthroat culture of active sabotage could.

. . . some managers didn’t see [rank-and-yank] as helpful, especially after it had been used for a few years and some competent employees were ending up in the bottom 10 percent. You can trim fat only for so long. Also, some thought that the policy made workers fight each other for survival and inhibited managers’ ability to bring their workers together to operate as a team for the good of the company. One manager tried to subvert the system by putting an employee who’d recently died in the bottom 10 percent of the ranking list in order to save another employee’s job.

Lights Out: Pride, Delusion, and the Fall of General Electric, by Thomas Gryta

The seduction behind solely focusing on performance is that it is simple and often works in the short term. GE grew substantially for years under this system. They were the most valuable company at one point in time with a market capitalization of over $600 billion. As of this writing, GE’s market capitalization is around $85 billion.

Long-term success requires trust.

If the SEALs, who are some of the highest-performing teams in the world, prioritize trust before performance, then why do we still think performance matters first in business?

The Infinite Game, by Simon Sinek

Warren Buffett’s Advice on Performance and Trust

Consider a thought experiment Warren Buffett posed to MBA students at the University of Georgia years ago that went like this: pretend that you’ve been made an offer where you could pick any one of your classmates and you’d get 10% of their earnings for the rest of their life. And conversely, you also have to pick another one of your classmates and pay 10% of their earnings. Effectively, select who will likely be the most and least successful people in the class.

What goes through your mind when determining who you’d pick for both instances?

Buffett says the following for selecting the person whom you’ll receive 10% of their earnings.

You probably wouldn’t pick the person who gets the highest grades in the class. There’s nothing wrong with getting the highest grades in the class, that just isn’t going to be the quality that sets apart a big winner from the rest of the pack.

And for selecting the person you’re paying 10% of their earnings, Buffett remarks:

Again, it isn’t the person with the lowest grades or anything of the sort. It’s the person who just doesn’t shape up in the character department.

After posing the hypothetical to the class, Buffett shares his own thoughts on the matter.

We look for three things when we hire people. We look for intelligence, we look for initiative or energy, and we look for integrity. And if they don’t have the latter, the first two will kill you, because if you’re going to get someone without integrity, you want them lazy and dumb.

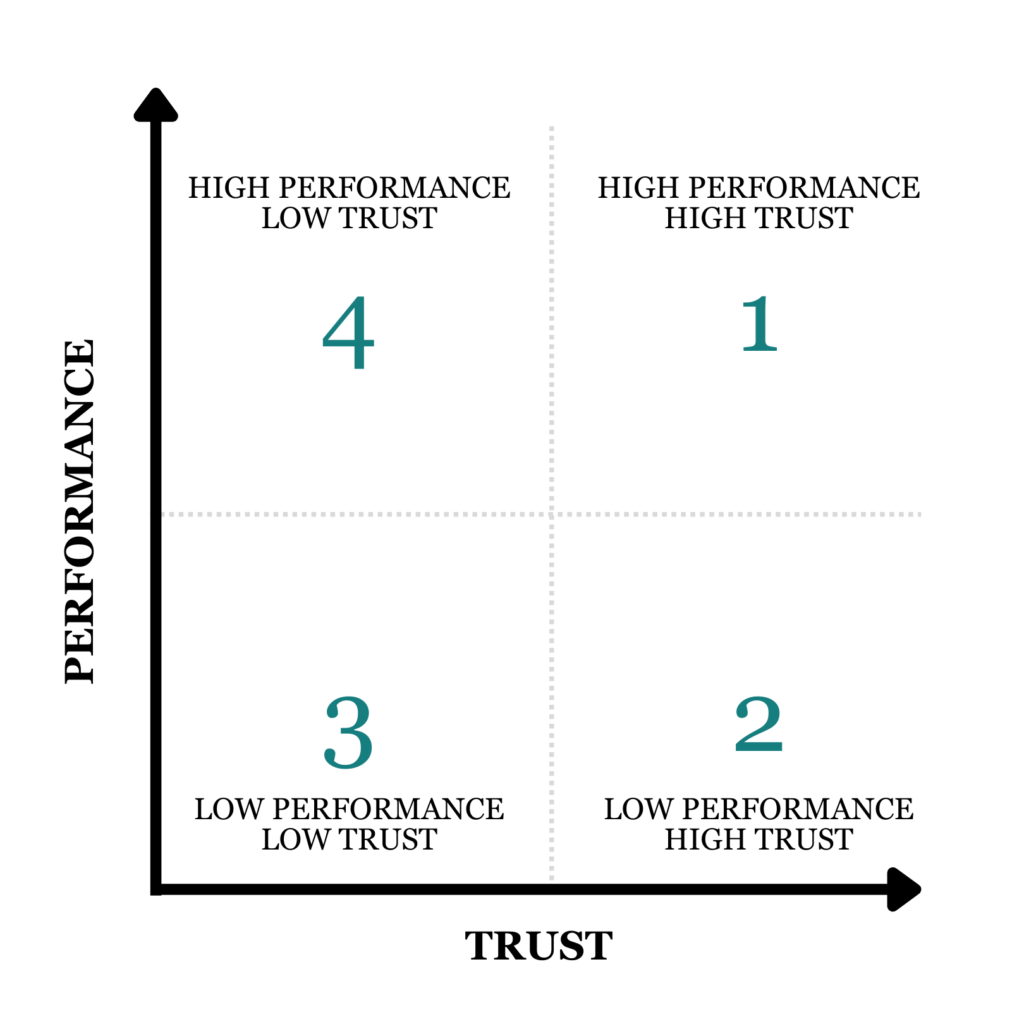

If you loosely define performance as intelligence plus initiative and substitute integrity with trust, you get a sentence that reads like this:

We look for high performers who are trustworthy. If they aren’t trustworthy, their performance will kill you. If you’re going to get someone who isn’t trustworthy, you want them to have low-performance capabilities.

In Buffett’s book, the priorities look like this.

Conclusion

Regardless of the actual order of the low trust cohort, one thing is clear: the important differentiator is trust, not performance.

As a team leader and team member, you have to look internally and externally when it comes to cultivating team culture. When considered internally, understand that others need to trust you. This requires vulnerability, empathy, and reliability. When considered externally, prioritize people for the team who are high in trustworthiness over their technical capabilities. Make it clear that acting in ways that don’t contribute to the team’s effectiveness is not acceptable. One of the most important factors for the team’s long-term success is trust.

Dealing with low-trust people is inevitable. In those situations, maintaining distance and treating the encounter transactionally offers layers of protection. Use them as an external resource with clear boundaries. But even then, it’s best to select high-trust people from the start.

The SEALs prioritize trust over performance. Warren Buffett does the same at Berkshire Hathaway. If valuing trust is a common thread in elite organizations, shouldn’t you elevate the importance of trust in your life?